For the exhibition ‘Building Echoes’, Colin Lindsay translated back into the three-dimensional a series of architectural elements from a single found book plate depicting Le Corbusier’s Villa Shodhan. Villa Shodhan was built in 1956 in Ahmedabad, India as a private home for mill owner Shyamubhai Shohdan. By placing the works Shodhan Screen, Shodhan Portal and Shodhan Hex Table and Chairs inside Interview Room 11, an artist-run space within Argyle House, Edinburgh, the relationship of Lindsay’s work to this particular context operates as a strange Brutalist matryoshka. Lindsay’s objects echoing Corbusier’s blueprint for Villa Shodhan are situated within a Scottish meme of Le Corbusier’s vision for urban planning. Argyle House, a 1968 office block originally providing accommodation for Government, was designed by architects Michael Laird & Partners [1]. Lindsay refers to this shared architectural lexicon as ‘trickle-down Modernism’. Basil Spence’s Hutchesontown C flats in the Gorbals, Glasgow, built in 1962 and demolished in 1993 are a further example. These buildings can be seen as urban poetics or city eyesore, dependent on the polarity of viewpoint.

Installation shot, ‘Building Echoes’, Interview Room 11, Edinburgh (2015). ‘Shodhan Portal’, ‘Shodhan Hex Table and Chairs’, ‘Shodhan Screen’, Colin Lindsay (2015). Photo: Colin Lindsay

With Le Corbusier as the original signal shaping both Argyle House and Colin Lindsay’s work, how is each encoded within its situation? Argyle House, which lies adjacent to Edinburgh Castle was described in a leaked City of Edinburgh planning document as a building which ‘dominated’ the surrounding area, asking for any new development to ‘respond meaningfully to the profile of Castle Rock’. [2] This document through implication refers to an antagonistic relationship through proximity between two very different eras of fortress. The latter, Lindsay’s installation within Interview Room 11, transforms the shell of an artist-led gallery into an integrated receiver, harmoniously arranged around the logic of the body and the eye. Corbusier in ‘Towards an Architecture’ (1923) states: ‘Our eyes are made to see forms in light; light and shade reveal these forms; cubes, cones, spheres, cylinders or pyramids are the great primary forms which light reveals to advantage; the image of these is distinct and tangible within us without ambiguity’. [3] The rules that Lindsay brought to the room allowed for a harmonious whole.

‘Shodhan Portal’, Colin Lindsay (2015). ‘Building Echoes’, (2015), Interview Room 11, Edinburgh. Photo: Colin Lindsay

Shodhan Portal is key in this particular transformation of space. Made from recycled wood and left raw and primitive in construction, its dimensions and portico are monumental in scale, offering grandeur to what otherwise is a BSI [4] standard door frame. Beatriz Colomina in her essay ‘The Split Wall: Domestic Voyeurism’ suggests, ‘In every [building] there is a point of tension and it always coincides with a threshold or boundary’. [5] Placed at the liminal point of the threshold, the portal’s presence transforms this normal environment into one which reaches for another ideal.

‘Shodhan Screen’ (2015), Colin Lindsay. ‘Building Echoes’ (2015), Interview Room 11, Edinburgh. Photo: Colin Lindsay

Lindsay’s approach to making is process-led, conducting a kind of archaeology of the image. Working from the found photograph of Shodan Villa combined three types of understanding or rules; the application of universally accepted principles, guess work and embodied knowledge. Some dimensions could be secured through BSI standards. For example, with the scissor chairs Lindsay used the accepted height of a chair. Others measurements were relational to the artist’s own body, such as his height compared to the potential height of the Shodan Screen. With Lindsay as the translator, the very act of making also allowed an insight into the decision process of the original transmitter, the architect. The architect Howard Roark in Ayn Rand’s novel ‘The Fountainhead’ (1943) looks at elements of nature and immediately translates it into the manmade, which he sees as having supremacy over the former:

“He looked at the granite. To be cut, he thought, and made into walls. He looked at a tree. To be split and made into rafters. He looked at a streak of rust on the stone and thought of the iron under the ground. To be melted and to emerge as girders against the sky”. [6]

However, to enter the physical space of the gallery is not to enter the photograph. Too much is retained of the architectural context of Interview Room 11 to allow for this work to be a direct replica of the Shodan Villa interior. The resulting work is rather a play between these objects and the context. Lindsay made some significant alterations to the gallery space, unblocking windows to let light and views from the outside in, and removing a free standing partition wall to allow for the flow of the space. He also chose what remained in terms of what features were to be amplified or hidden. There are four doorways that exist within the space; the gallery entrance; the original interview room the gallery takes its name from; the gallery office; and the introduced smaller Shodhan portal on Shodhan Shed. The recycled materials and natural colour palette that Lindsay uses to transcribe Corbousier’s Shodhan Screen, portal, chairs and table play off the weirdness of the modern office materials of ceiling tiles and woodchip, lending a precision to the surroundings. By introducing elements from a very different kind of space for living, Lindsay is playing with the notion of the artist-led gallery which can humbly spring up in any empty interior, like the hermit crab who inhabits another’s shell.

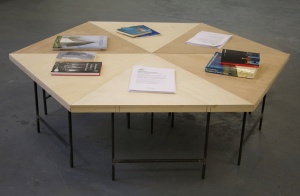

‘Shodhan Hex Table’ (2015), Colin Lindsay. ‘Building Echoes’ (2015), Interview Room 11, Edinburgh. Photo: Colin Lindsay

A further element which moves the installation away from the original and the photograph is the heightened embodied experience of the gallery visitor. In a sense Lindsay’s work makes the original Shodhan House inhabitable and publicly accessible. The owner of the original has kept the house private throughout the lifetime of the building. Passing through the Shodhan Portal, the interiorscape of the gallery opens out as a strip, curving out in front of the viewer. Walking to the end of the space, past the seating area, the screen and hut, the person looks out of the windows only to perceive that the floor they are standing on and room they are in is suspended in space. Looking around, the eponymous cladding of white walls are dotted with the past marks of nails and pins. Interview Room 11 also retains some features of its past use. There are columns or totems of computer plug sockets. Areas of wood chip wallpaper stubbornly hold onto some of the pillars. A low polystyrene seventies tile ceiling is mostly intact. Sections have been removed to reveal segments of bare neon tube lighting. A sequence of opaque pyramid roof lights dot through the space also. There is an omnipresent buzz of the building beyond. A far off door shuts. As the pages of suggested reading matter are turned at the Hex desk, the wind whistles off the Castle’s volcanic plug and echoes in a loose fitting window and pipe. Strips of plastic bags are caught on the branches of trees outside, making an informal wish tree.

Within this setting, The Shodhan Screen takes the visual form of Corbusier’s brise-soleil; a wall divider with built in sun screen apertures to allow for ventilation, creating the opportunity to bring the outside in. This interplay of interior and exterior is also represented with Shodan Shed, which lies at the centre of this Brutalist Russian Doll. It is the only element introduced by Lindsay that is not directly taken from the photograph of Villa Shodhan. The doorway on such a humble shelter has been given a smaller version of Shodan Portal. The side is clad in a single unit of the brise-soleil design. For Lindsay this structure is reminiscent of a chantry chapel or altar, a little building of difference, built inside a larger building.

Lindsay has been working on what he calls ‘parallel objects’ over several years, with recent sculptures that refer to designs by Breuer, Rietveld and Le Corbusier. Whilst these sculptures use the original as a blueprint, their transcriptions through material and intention are neither copy nor reproduction. Time, distance, site and the evident craft skills of Lindsay make these works unique rather than a simulacrum.

“Rules?” said Roark. “Here are my rules: what can be done in one substance must never be done with another. No two materials are alike. No two buildings have the same purpose. The purpose, the site, the material determine the shape. A man doesn’t borrow pieces of his body. A building doesn’t borrow hunks of its soul. Its maker gives it the soul and every wall, window and stairway express it’. [7]

‘Building Echoes’, Colin Lindsay, Alberto Condotta, Interview Room 11, Edinburgh 16-31 January 2015

Footnotes

[1] Argyle House also complies with Le Corbusier principle of erasing the past, co-existing in proximity only, with the 700 million year old extinct volcano of Castle Rock and Edinburgh Castle. Laird & Partners, the architects of many buildings across Edinburgh were innovators of the possibilities of a building sustaining itself. Laird designed the Computer Centre in Fettes Row for the Royal Bank of Scotland, reusing the energy from its computers to heat the offices. The architects also commissioned artists as part of their buildings. There is a John Bellany mural in the building of the White Fish Authority; an Eduardo Paolozzi at the RBS building in South Gyle and work by Gerald Laing at the Standard Life Building. With artists and creative organisations housed in Argyle House in present day, it is pleasing that artists are once more located in this building.

[2] ‘West Port / Kings Stables Road Development Brief’, draft for consultation, Planning Committee, City of Edinburgh Council, 6 August 2009.

[3] Corbusier in ‘Towards an Architecture’ (1923)

[4] British Standards Institute was established in 1931 after work since 1901 by the engineering Standards Committee to bring in standard sizes to goods such as iron and steel being manufactured. The Architects Journal Handbook contains regulatory and legislative guidelines relating to building structures and standardized measurements.

[5] Beatriz Colomina, ‘The Split Wall: Domestic Voyeurism’, ‘Sexuality and Space’, Princeton Papers on Architecture, Princeton Architectural Press (1992), P.95.

[6] ‘The Fountainhead’, (1943) Ayn Rand, P.16, Penguin Modern Classics.

[7] Ibid, P. 30.