Workspace, Dunfermline, 5 December 2015

The public art rolls past the bus on the way from Glasgow to Dunfermline. Yellow metal gills appear on each side of the embankment along the gateway to Cumbernauld, mirrored in mint green on departure. Roundabouts, the 1980s’ plinths for stainless steel aberrations, proliferate like daisies.

One of the passengers is deep in monologue. “She shut the door of the kitchen down and knocked that wall down. See the stairs? Take that bit of the wall down – get me, right? …Naw, naw, Sandra has got a false wall back to the stairs, so then, get what I mean? Sandra’s doors at an angle and that’s right back and she’s got her kitchen door there – and then they’ve half shut the wall – do you understand where I’m coming from…. Yer still coming up the stair. The wall’s there and she’s got her door put back at an angle.”

The woman is beginning to get exasperated. Her friend who is sitting next to her is not following the intricacies of Sandra’s door alterations that gained her extra inches in the house layout. “Oh we’re at the seaside, girls”, she says sarcastically as the bus goes over the Kincardine bridge, with Longannet Generating Station in the foreground and the chimneys of Grangemouth Refinery on the far shore. “It would look much nicer with the sunshine out. Oh there it is! Glittering on the water!” A pause and a mindful moment for all on the bus.

The woman begins again. “I mean I cannae do it any more, I ‘m tired of it! I’ve had my ceilings all lowered and it’s plastered now. I can’t take them out like Sandra has. I’m getting older, I cannae just…” We pass a bearded man in a red top standing in a lay-by. He is videoing a field with his camera arm aloft. The field doesn’t look too extraordinary. He is in his own mindful moment.

~

I am on a trip to see Alan Grieve and find out more about his own approach to mindfulness linked with his new work about a cemetery in Dunfermline. If mindfulness is focusing on the breath in the body, there is nothing like a graveyard to help someone keep breathing and present. Alan passes through the cemetery every day when walking his dogs or on his way to work. Like the nuanced altering of angles of Sandra’s doors, much of Alan’s work is about making small yet satisfying shifts in language, drawing and object making. The subject of the graveyard is proving to be highly conducive for moving meaning from one realm into the next. He shows me his sketchbook. A page is emblazoned in felt tip with the phrase “Who put the fun in funeral?” He explains that he has been considering this as the title for the book he is working on, but other people he had tested it out on thought it too much.

Alan is an adult man who has been thinking about colouring-in of late. He is not alone, as companies have re-spun kids’ colouring-in books for ‘grown-ups’, providing nostalgia to those who grew up in the sixties and seventies’ and are now stressed in the noughties. Mindfulness, a concept not readily known to most Scottish households before the Millennium is on the increase. Using his boys’ felt tip pens, Alan has been making drawings for the last two months, in the quiet time every morning before his kids and wife gets up.

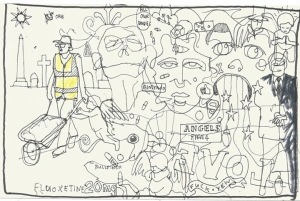

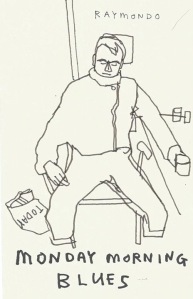

The drawings are multiplying- creating their own universe- and are a tour de force. A core of the work is dedicated to the graveyard operatives Raymond and Garry, with whom Alan speaks in passing every day. Bringing the two men centre stage is a key component, as this is a role which otherwise would normally fade into the background. In one drawing, Alan shows gravedigger as gladiator, riding the trailer around the huge graveyard as if it were a chariot. He also captures the more mundane moments such as the younger gravedigger nursing a Monday hangover. The veil between this life and the next is shown as the spirits stream behind the older grave digger who pushes a wheelbarrow in his council hi-vis vest.

The trees, the play of light on the leaves, the animals, the stonemasonry, the unusual names and stories. It can be quite easy for the brain to slide away from the real purpose of the cemetery. Mindfulness here is mortality, so Alan ensures fresh death is never too far away in the drawings. Some feathers litter the foreground of a pastoral scene with weeping willow and gravestones. A candle is lit for all the unborn babies. Alan’s drawing skills are a joy to behold, ranging from the juvenile with an adult’s knowing (like those drawn by bad boys on the back of girls’ school jotters), to technically excellent renditions of stained glass windows in three thicknesses of pen.

There are some I wish I could un-see such as the skeleton locked in a carnal embrace with a human. The macabre is ever-present. A council skip overflows with dead bodies under the Pac Man motif ‘GAME OVER’. Other drawings are delightfully observational; a dignitary with a bad back uses the memorial headstone to bend down and place something on the ground. A beautiful old oak tree is captured in its glory, but look down to the right of its trunk and a Labrador is defecating. The scourge of pavements and graveyards it seems, is not picking up.

Even the animals of the graveyard are not always nice. Whilst some are sage, offering words of wisdom to the humans, others are plain ‘raj’. ’Fuckin’ mon then!’: a bat screams as it gives a full frontal to the viewer. Epitaphs are freed from celebrity gravestones. A hawk appears next to Spike Milligan’s ‘I told you I was ill’. There is a heightened sense of awareness in some of the drawings. Caught in an awkward cycle, a naked young man kneels amongst the toadstools, reaching out with an urn in his hand to catch the shite from a bird sitting above him on a branch, whilst a rabbit looks on. In another, the moon and sun explore their senses together, nestling in to kiss with no tongues. These are hallucinogenic scenes but contain their own sense of order.

Whilst order can also be found within the graveyard- the lines of graves and neat grass edges- there is no getting away from the disorder of death even down to the detail of who turns up at your funeral or how you get there. In one drawing, a man uses a Vauxhall Chevette estate to bring his wife’s coffin in to the cemetery. This was a story Alan heard from the gravedigger. In another, the Provost, Minister, and representatives of various community groups stand dignified at a Remembrance Day service. Alan has helpfully detailed each group with their nomenclature. In the back of the crowd one man is labelled with the title ‘random cunt’. There is definitely a contemporary gallows’ humour lurking within the work.

In a second strand of work, scenes of old Dunfermline depicted on old black and white postcards are helped into a trance with Alan’s bold colouring in. Frater’s Hall window panes are treated to the full range of post-it note colours of orange, green, yellow and pink. This stained glass rendering for the modern day church enthusiast is emblazoned with the colloquial epitaph of ‘windaylicker’. In another postcard, Dunfermline Abbey is cast as a version of the Emerald City with rave neon headstones.

Alan gives mindfulness a reality check. The phrase, ‘I wish I had the courage to live a life true to myself, not the life others expected of me’, would perhaps be expected as an insight from the pages of Psychologies magazine, illustrated by a pensive blonde haired Nordic woman with her eyes on Nirvana. In Alan’s drawing however, it is accompanied by a cheerful man with a heightened fringe aided by hair product. He is denoted as a worker as he wears a high-vis jacket. I like this, for whilst being gently subversive it shifts the kind of person such a declaration could be associated with. It also firmly places philosophy in the domain of everyone, not just those that have the luxury of time. Death, as the old adage goes, is the greatest leveller.

Alan’s stream of drawings are like the thoughts and feelings that occur from one moment to the next. Given the sheer exuberance and cacophony of voices that inhabit Alan’s cosmos, this mayhem could defy the calmness of mindfulness. However, to look at the drawings such as ‘Man with head in his hands’ (2015) or ‘Life Drawing’ (2015) where the pen does not come off the paper, there is the same kind of perfection of focus and concentration on the line rather than the breath. Some may quake at the foul language or perceive that some of the imagery is disrespectful in its mash-up of beliefs, but this loss of control or undermining of order cannot be ignored. It is fully present in the lives that we lead and the manner of that which awaits us. Simon Critchley’s excellent ‘The Book of Dead Philosophers’ (2008, Granta Books) details what the great philosophers wrote about death next to how they actually died. For example, Roland Barthes got run over by a laundry truck.

The exhibition ‘Cemetery’ and a mindful evening event were held at Workspace, a hairdressers and gallery that Alan set up with fellow hairdresser Emma McGarry in 2011, the same year as Hurricane Bawbag hit Scotland. Indeed, ‘Bawbag Memorial’ (2014-15) forms the centrepiece. It is a monument crafted from all the plastic flowers unmoored and blown amok in the Dunfermline cemetery during the winter hurricane that became an internet sensation due to its irreverent name. The plastic flowers will never die. This outsize floral tribute, reaches to the ceiling from its specially built platform. It is surrounded at its base by tea tree lights; that fragile marker of a departed soul, ubiquitous with church alters, make-shift street shrines and massage parlours. This is all set off by the saffron robe orange of the specially painted back wall and a single monochromatic collage called Deity, of Alan’s own young colleague James, who is angelic in his page boy haircut, nose ring and flesh tunnels. On the wall to the right, there is a huge mandala-like drawing completed in chunky black pen. It combines many of the images from the smaller drawings and is thoughtfully pinned up for the gallery goers to colour-in on the mindful night. Music by Dunfermline musician Dan Lyth permeates and amplifies the strange spiritual air in Workspace, encouraging the visitor to spiral into its repetitive groove.

The full range of doctored Dunfermline postcards hang within a grid network. Many stand out as an alternative reading of some of the town’s better known architecture. In a futile act of resistance to modernity and consumerism a Gothic turret from the city centre shouts ‘Fuck Primark!’ En masse, Dunfermline is definitely at the centre of the universe. Alan has also worked with recent curatorial graduate Kari Adams to make a wall hanging comprising of six of the postcards. With an all seeing eye at its apex, the borders of this piece have been edged with sequins and beads, and tasselled at the bottom. Fetishizing the postcards in this way as a worshipful artefact, works in this atmosphere of the retreat. Workspace is by no means the first retreat in Dunfermline. The glen that lies at the centre of town boasts Malcolm Canmore’s tower and his wife Margaret’s cave, where she took to for prayer.

The most unavoidable piece in this exhibition, ‘Wee Willy Windchimes’ (2015) is satisfyingly hung bang in front of a sewn patchwork of drawings which are enticingly detailed, thus making the viewer strain forward to view them. The obstructive positioning of these phallic windchimes makes them nigh on impossible to ignore. Their adult nature has freed them from the original reference. The historic and sad gravestone of Willie Dick lies in the cemetery and tells of a child who was killed by a shotgun mistakenly going off. These windchimes have been fashioned from a felled cherry tree from the cemetery and have been turned at a local workshop. If they had been painted pink they would have been too cartoonlike but in their unadorned state the viewer cannot but help admire the craftsmanship of the polished wood. As a piece of work it symbolizes Alan’s ability to mix both the poetic and prosaic with the profane.

~

I’m back on the bus on this wintery day to return to Glasgow. It is pitch black outside and rush hour. The bus crawls its way back in a slow moving queue up to the Kincardine Bridge. Reflections from the car headlights from the other unclogged lane skite across the bus interior. The pristine bobbed woman in the seat front is talking at her mother down the phone, about whether a metal or plastic carrier would be better for her cat in the event of a crash (answer is metal). I require a mindful moment as this feels like it will be a long haul. As the cars in the other lane zip past they begin to sound like waves on a shore, regular and relaxing, with the trucks as the big breakers. The lights of the power station twinkle like tea tree lights through the petrified trunks of the forest.

Jenny Brownrigg, Dec 2015