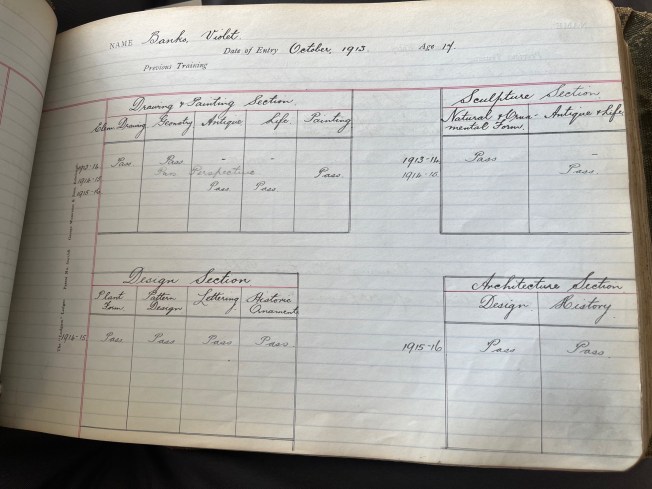

This visit has allowed for further work on Violet Banks’ (1896-1985) timeline. The Edinburgh College of Art Student Record book (1908-1920)[1] records Banks studying there from 1913-1916 then 1917-1918. Her date of entry is listed as October 1913 at age 17. Banks was predominantly in the Drawing and Painting section. It is listed that she also studied aspects of Design from 1914-15 and Architecture in 1915-16. She received her diploma in Drawing and Painting in June 1918. Two of Banks’ peers who received a diploma in same year were Anne Redpath (1895-1965) and Dorothy Nesbitt (1895-1971).

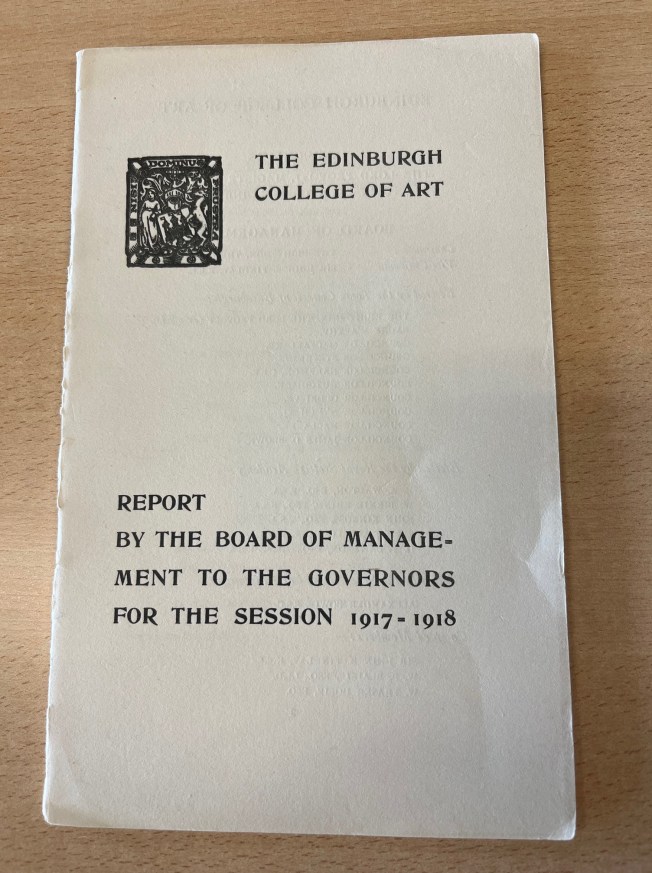

In the ‘Edinburgh College of Art Report by the Board of Management to the Board of Governors 1917-18’, Banks is recorded as one of two students who received a minor travelling bursary of £15. The minor travelling bursary appears to have allowed the recipient to undertake visits to art collections, with a stipulation to present drawings from those on return. In the 1917-18 report, the quality of Banks’ work is recorded as follows:

‘The Head of Section reports that although conditions in regard to closed Galleries and sketching restrictions were as is, in the previous year, a creditable amount of work was done, thoroughly justifying the award. He states that the work of Anne Redpath while less in quality than that of Violet Banks, was of a very high standard, probably the highest yet reached by any Minor Travelling Bursary.‘[2]

In the Report from the following year, it shows Banks’ fellow students Redpath and Nesbitt go onto get their post-graduate qualification[3]. However, under the heading ‘Appointments to Students of College During Session 1918-19’, Violet Banks has been listed as ‘Art Mistress, Brondesbury House, Kingsgate, Thanet, Kent’.[4] This is the first record of her having spent time out with Scotland. Barry J. White’s ‘Thanet’s Private Schools 19th and early 20th Century’ (2004) lists Brondesbury House as a small girls’ boarding school in Margate, at 2 Eastern Esplanade. It is not currently known how long she stayed, but it looks like her first art mistress position before she was a senior art mistress at St Orans, Edinburgh[5].

To return to the Student Record book, in Banks’ entry it states she ‘Went into the studio of McLagan & Cumming 1928.‘ This was a printers, lithographers and photography studio in Edinburgh.[6] It is interesting to consider whether this experience of potentially working in photography studios gave her the experience to establish her own photography studio in 1930.

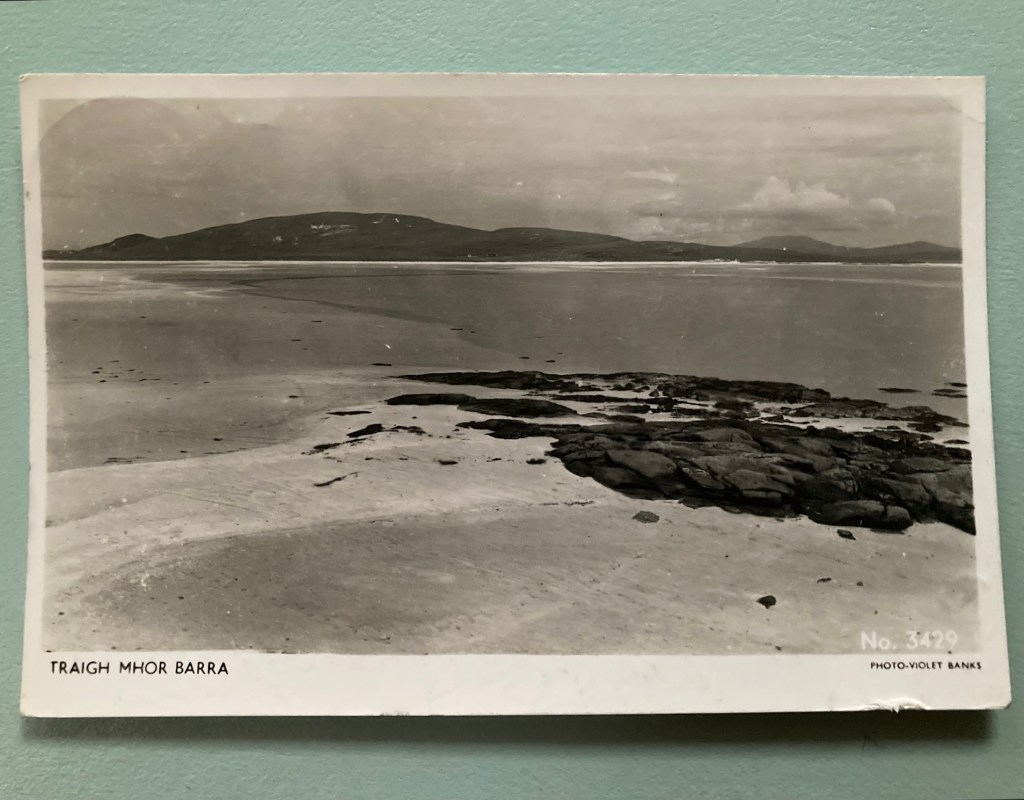

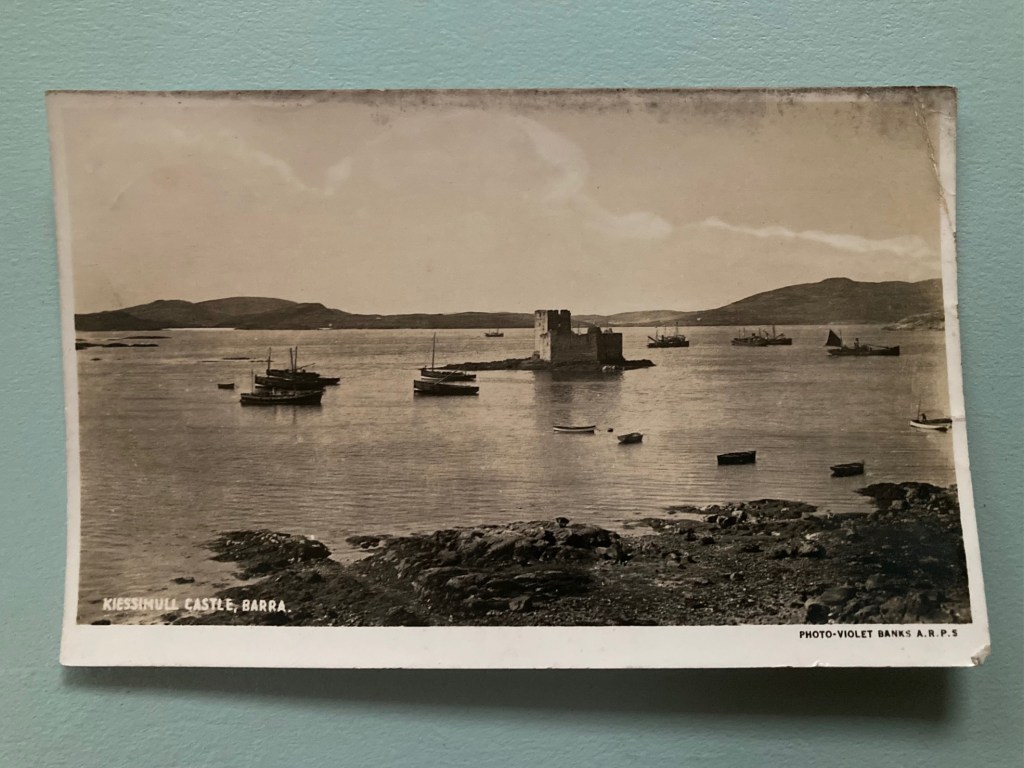

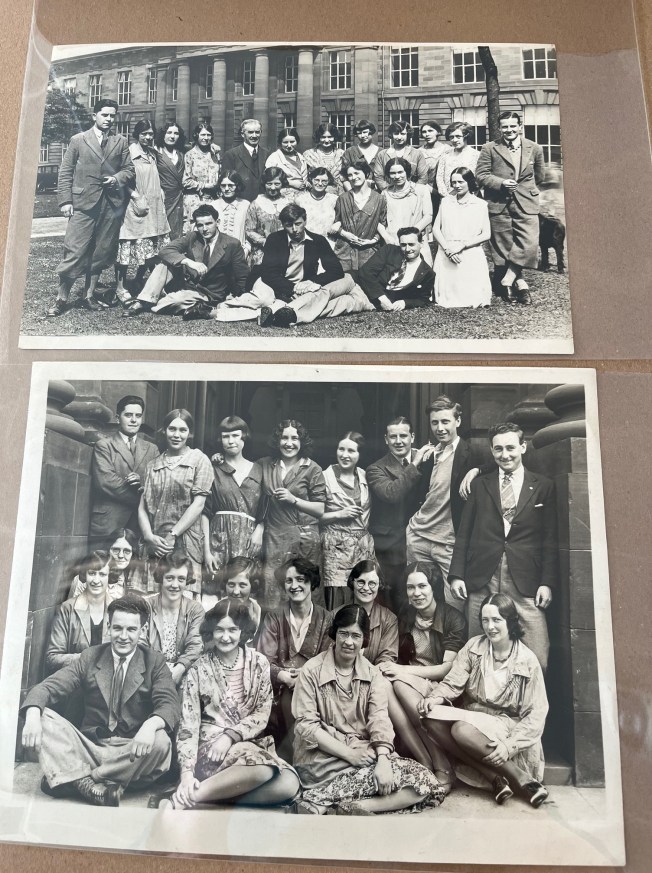

The final items relating to Banks held at University of Edinburgh Heritage Collection are seven photographs, stamped on the back with ‘Copyright Violet Banks A.R.P.S. 11 Randolph Place Edinburgh‘. They are noted as being Diploma Photographs, ranging from 1930-1933, showing students from Edinburgh College of Art Design group and Drawing and Painting as well as Design sections. On the back of the 1933 photograph there is a note of costs: ‘Copies 2/- each / Copies matt and mounted 2/6′. This suggests copies were for sale, potentially to the graduating students and their families. These photographs show that 12 years after her own graduation, Banks had returned to Edinburgh College of Art as a jobbing photographer for a commercial opportunity.

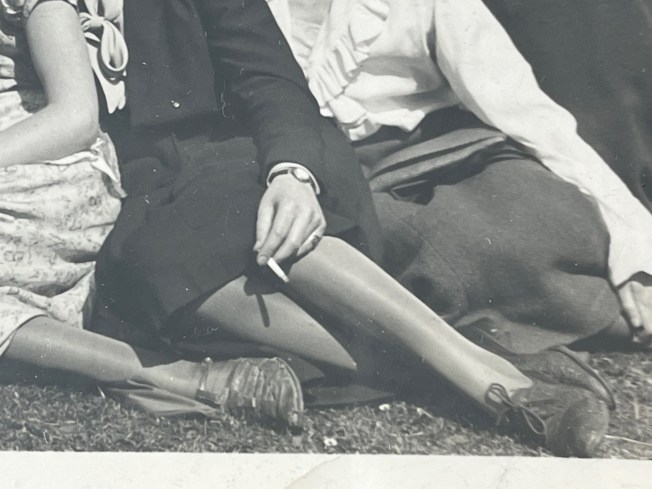

The photographs of the students are informal. Whist the students are in rows, in the 1930 photograph the women students are mostly still wearing their overalls. Banks captures the group’s camaraderie, with their arms around shoulders of peers. In 1932’s class photograph, one of the women is smoking. When contrasted with a formal class photograph by Drummond Sheils depicting the 1932 Architecture Diploma group, there is a marked difference in photographers’ approaches. Whilst Banks’ class photographs are outdoors and natural, the Sheils grouping sees the students formally sat in chairs. All are wearing gowns and are unsmiling.

Violet Banks Collection is at Historic Environment Scotland. Her work is also part of the IF Grant Collection at Edinburgh Central Library, The Museum of Childhood, Edinburgh and National Galleries of Scotland. Out of the 14 women photographers and filmmakers in ‘Glean: Early 20th Century women filmmakers and photographers in Scotland’[7] she is only one of three to have had an art school education[8]. Banks’ trace in the student records and reports at University of Edinburgh has given further crucial information on her biography.

Footnotes

[1] ECA/3/2/1/1, Student Record Book, 1908 – 1920, University of Edinburgh.

[2] ECA/1/1/1/10, ‘The Edinburgh College of Art, Report by the Board of Management to the Governors for the session 1917 – 1918′, University of Edinburgh.

[3] ECA/1/1/1/11 P.26, the ‘Edinburgh College of Art Report by the Board of Management to the Board of Governors 1918-19’, University of Edinburgh.

[4] P.27, Ibid.

[5] https://www.nationalgalleries.org/art-and-artists/artists/violet-banks

[6] Glasgow Museums collections navigator.

[7] City Arts Centre, Edinburgh (2022/23), curator Jenny Brownrigg.

[8] Margaret Watkins (1884-1969) studied with Clarence H White at his schools in New York and Maine. Helen Biggar (1909-1953) studied textile design at The Glasgow School of Art.

With thanks to Heather Jack for providing the catalogue references and steer to visit University of Edinburgh Heritage Collection.