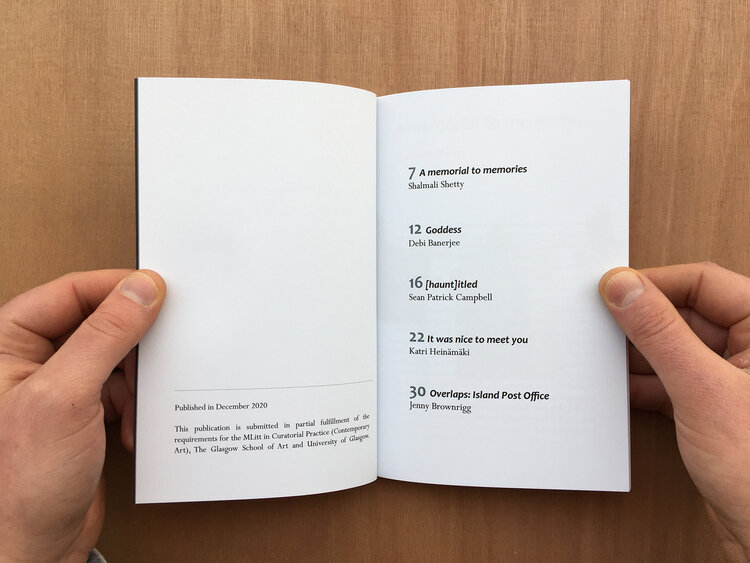

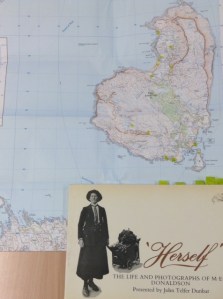

Thanks to a weeklong residency at Sweeney’s Bothy, I was able to visit the Isle of Eigg for the first time. My main aim was to seek out the places that MEM Donaldson photographed on her visits to Eigg, between 1918-1936. Her photographs illustrated her travel guide ‘Wanderings in the Western Highlands and Islands‘ (1921). The week also became a time to look at a second Scottish photographer, Violet Banks [1] and her photographs of Eigg from her tour of the Western Hebrides c. 1920s & 30s’.

Map of Eigg, green arrows denote sites Donaldson photographed Photo: Jenny Brownrigg (2016)

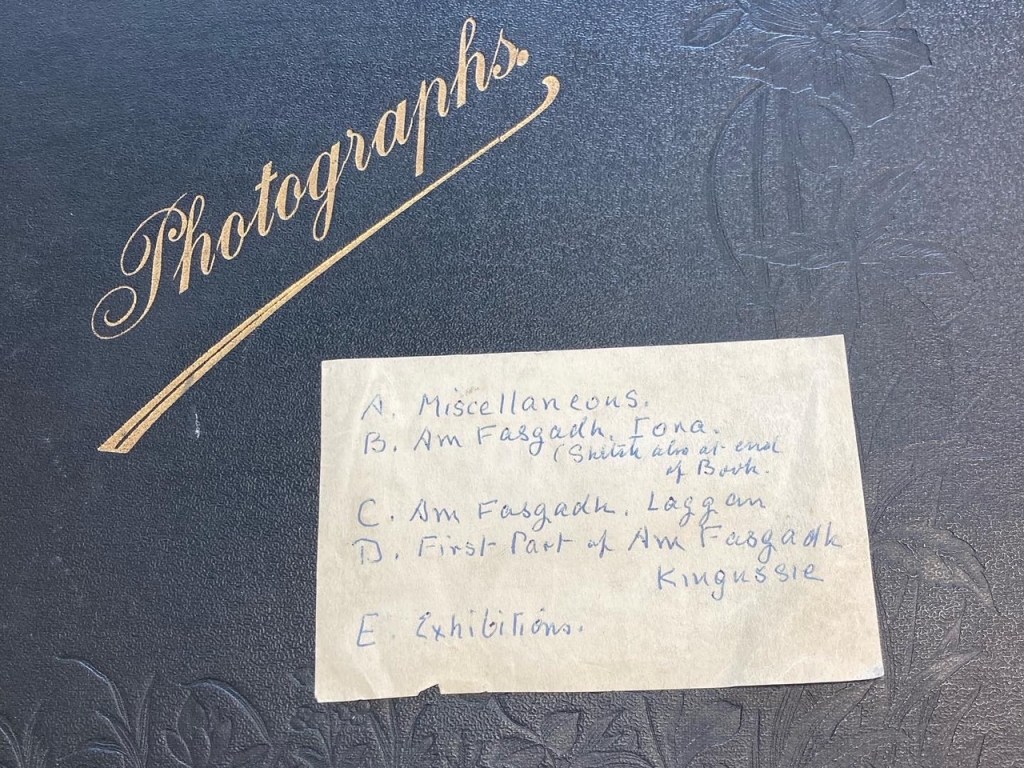

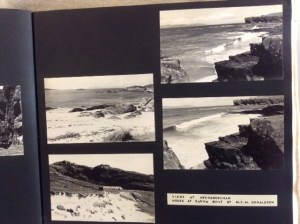

Intriguingly, Donaldson and Banks’ paths may have crossed at Donaldson’s distinctive home in Arnamurchan. In a set of black photograph albums held at Royal Commission of Ancient & Historical Monuments of Scotland, Banks dedicates one section to Ardnamurchan, with a page of four photographs captioned ‘Views of Ardnamurchan, House at Sanna built by M.E.M. Donaldson‘. Banks frames the low buildings of MEM Donaldson’s home in the middle distance, nestled with a small hill behind and close to the edge of a low dune. The photograph with caption provides the first physical evidence that one photographer is aware of another, amongst the women who I have been researching that documented Scottish Highlands & Islands life in the inter-war years.

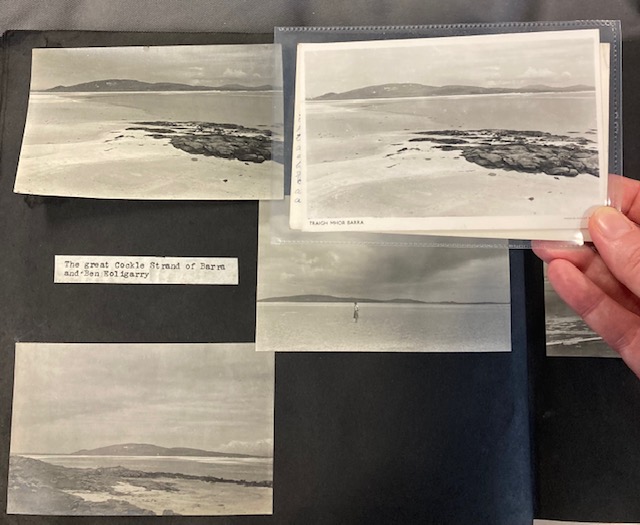

Detail from Violet Banks’ photograph album, Royal Commission of Ancient & Historic Monuments Scotland Ref: PA244

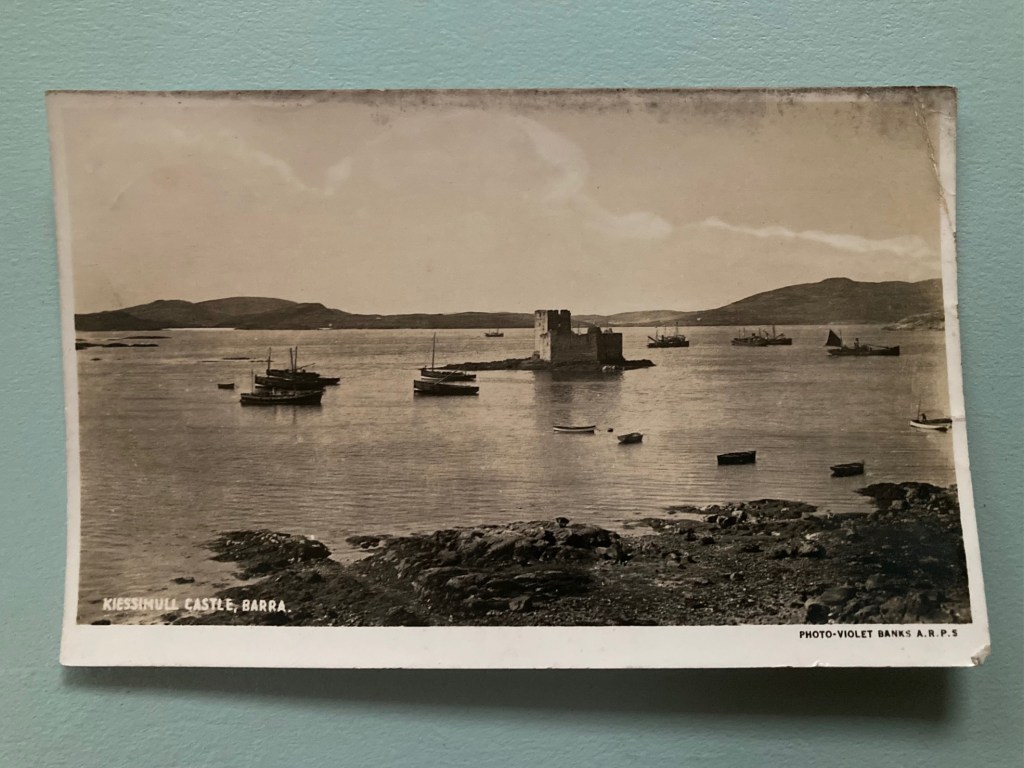

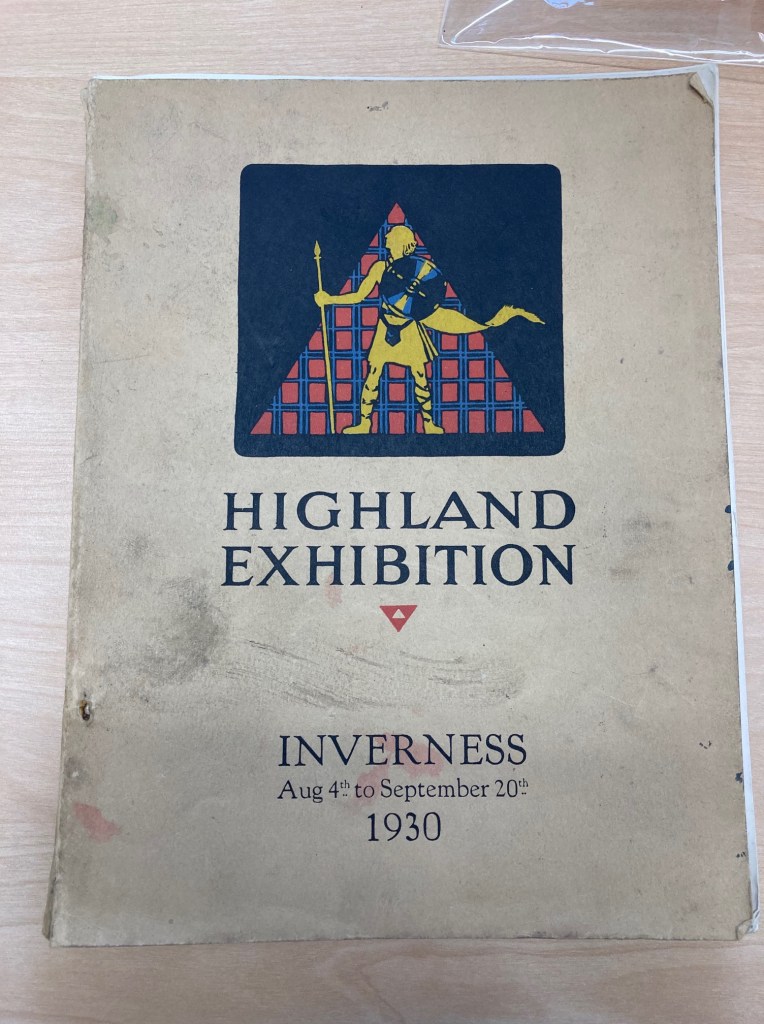

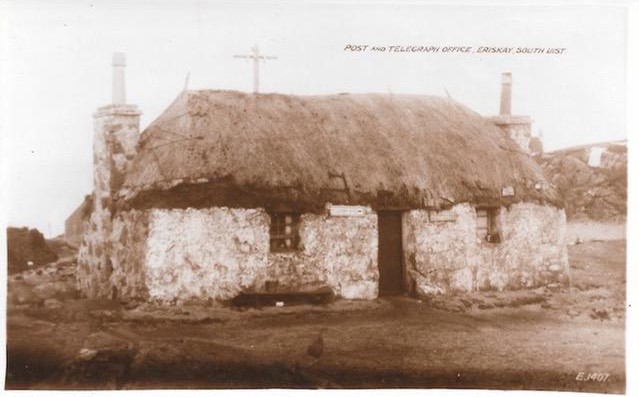

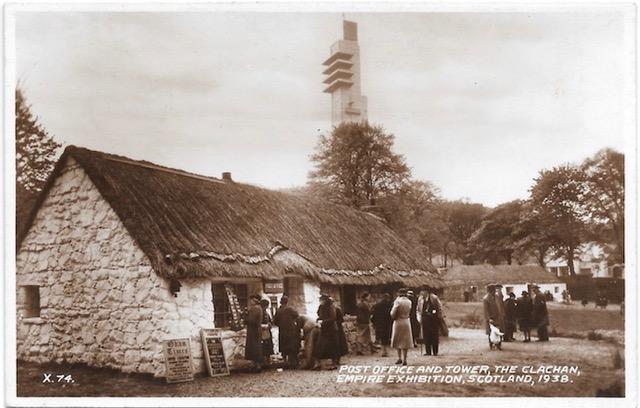

Banks also visited and photographed a number of locations that Margaret Fay Shaw captured too, including the Telegraph office at Eriskay, and also a Highland Games featuring Compton Mackenzie in a line of judges at Northbay, Isle of Barra. The photographs have a similar framing, yet the seating arrangement and Mackenzie’s flamboyant dress as a chieftain is different in each photograph, so may not be taken at the same Games.

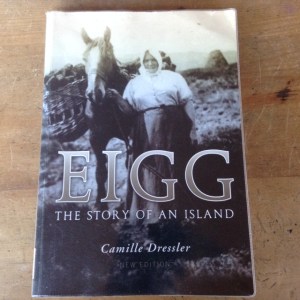

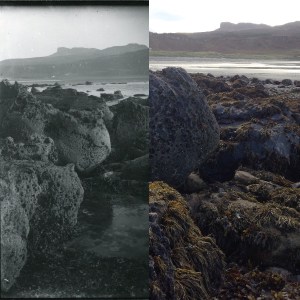

On the Saturday ferry over from Mallaig to Eigg, I showed digital images of MEM Donaldson’s series on the island to Lucy Conway (the host of Sweeney’s Bothy with her husband Eddie Scott) and another islander, Eric Weldon. They immediately helped identify locations. A further resource has been the impressive, ten years in the writing, ‘Eigg: The Story of an Island‘, [2] by local resident Camille Dressler. This book is part of an excellent compact collection called the ‘Walking Library’ [3] at Sweeney’s Bothy. Dressler recounts that Donaldson stayed at Laig Farm, on her visits to Eigg, which in that period as well as a working farm was a Temperance Hotel. [4] Two of Donaldson’s photographs show the farm. The first shows the start of the path down to the farm, with the gateway at the side of a cliff-face. The second denotes Laig Farm’s grouping of low buildings, in a small valley with a sandstone headland rising behind [5]. Laig beach, close to the farm, is the site of third photograph, which shows a woman, likely Donaldson’s companion, the illustrator Isobel Bonus, walking along the gray sands. The distinctive silhouette of the island of Rum lies on the near horizon. Donaldson takes another photograph at this location; a detail of the strange fossilised stones found at the south end of Laig beach.

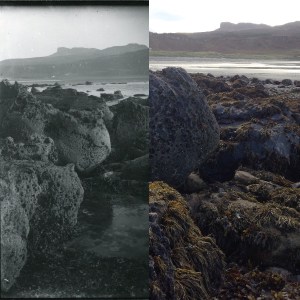

(l) Detail of ‘Coast of Eigg, Sgurr in background’, MEM Donaldson, Ref: 958.20.505, Inverness Museum & Art Gallery. (r) Photo: Jenny Brownrigg (2016)

Like Laig Farm, a good number of the photographs are dotted around Cleadale itself, where Sweeney’s Bothy is located. Donaldson was drawn to ‘sites with historical associations’ [6]. She photographed two local children, Joanne MacLellan and Katie-Ann MacKay fetching water from St Columba’s Well [7] at Cleadale, where one can still take a drink of its cool, clear water, credited with healing powers, from a generously provided mug. (Lucy tells me later that this is the water for both drinking and showering with at Sweeney’s Bothy!) The well was said to be blessed by Colm Cille and believed to prophesize the fate of those children baptised in it, from the ‘number of rivulets running down’ [8]. Perhaps this story prompted Donaldson to photograph the two girls at the well. Further around the coast, in another photograph, a white bearded islander, Lachlan MacAskill points with his stick to St Donnan’s ‘pillow’ stone, lying in front of the ruins at Kildonan Church.

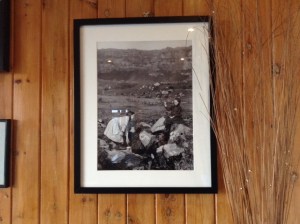

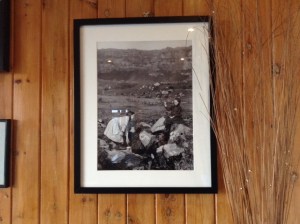

Framed MEM Donaldson photograph of children at St Columba’s Well, Eigg, exhibited at Galmisdale Bay Café and Bar, Eigg

It is important to note that we read these images differently, according to our own experience. I am a similar audience, thanks to where I live, as Donaldson’s main readership was. Hugh Cheape asserts that as her photographs were to illustrate literary work, the perceived audience would have been those who were ‘probably town-based’. [9] Before my visit to Eigg, this series of photographs had their only identifiers of location as the general catalogue credits from Inverness Museum & Art Gallery Archive, which was enough to bring me to Eigg. Local knowledge shared during this residency, has brought the photographs into a new focus. The image of a woman, possibly Isabel Bonus, with knapsack on her back, walking along a track was identified as being at Cleadale, ‘round the corner by the quarry‘. A traditional cottage and byre are identified as ‘Mairi’s house and shed‘. Dressler when looking at the same photograph pointed at the stone in the foreground and recounted that a previous owner, an old man, ‘always used to always sit on the rock’. For the island resident, the photographs are coded in a different way, moving naturally to the detail such as who currently owns the croft pictured. Sometimes the information that stands out in a local reading is an anomaly in the landscape. For example, it was remarked that it was ‘unusual to have a boat there’, in another photograph.

(t) Detail, ‘figure, Miss D probably, on road in Eigg’ Ref: 958.20.185, Inverness Museum & Art Gallery (b) Photo: Jenny Brownrigg (2016)

Both Donaldson and Banks photograph key landmarks on Eigg, in particular An Sgurr, the distinctive pitchstone outcrop, which the highest point of the island; also both photograph other ‘tourist sites’ at the Massacre and Cathedral Caves. Donaldson’s photographs of An Sgurr place it within the context of one of her walks, showing the approach to it from a route than can be traversed across a plateau. Banks chooses to show An Sgurr by placing a woman in scale with ‘the Nose’. Both Donaldson and Banks also separately photograph the loch to be found en route to the Sgurr, known as Loch nam Ban Mora – ‘Loch of the Big Women‘ – where the submerged causeway to the crannog in the middle could only be forged by a race of women of ‘supernatural proportions’. [10] The name refers to the Queen of Moidart’s warrior women, sent to murder St Donnan and his monks on Eigg. Lights from the dead bodies of the monks bewitched the women, leading them up to Loch nam Ban Mora, and luring the women one by one into the water, with all drowning. Both Donaldson and Banks also photograph the Sheela-na-gig, at Kildonnan Church. Sheela-na-gigs ‘are carvings, often found in churches, which consist of a female displaying, or drawing attention to, her genitals‘. [11] Alasdair Alpin MacGregor also photographed the Sheela-na-gig on his visit to Eigg.

(t) Detail from Violet Banks’ photograph album, Royal Commission of Ancient & Historic Monuments Scotland Ref: PA244 (b) Photo: Jenny Brownrigg (2016)

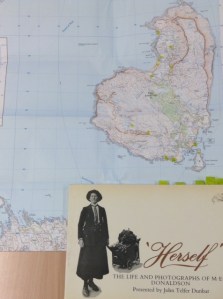

Donaldson’s work in particular has very much been given its place in Eigg, represented in (photo)copies of her work held in the photographic collection at Eigg History Society Archive and in Dressler’s writing on Eigg. Donaldson’s photographs can be found framed in the Galmisdale Café and Bar. This archive gives the unique opportunity to view Donaldson’s work alongside other vernacular historic photography collections, amassed from photographs by islanders, held over generations, in an ‘Awards for All’ project led by Eigg History Society (Comunn Eachdraidh Eige) for the Eigg Trust, started in 1997. Taking an example, one of Donaldson’s photographs is captioned by John Telfer Dunbar in ‘Herself‘, a biography, as ‘taking the peats home’ where ‘the woman with a white kerchief tied round her head is described as ‘the embodiment of good nature, health and contentment’. This woman is named in a photocopy of this photograph held in Eigg History Society Archive as Ishbel MacQuarrie [12]. Donaldson photographs MacQuarrie at work, but also her home, which may for Donaldson signify the changing traditional architectural vernacular of the Highlands and Islands. The caption for this photograph in the archive relates to the disappearing history that the architecture represents and an anomaly which may interest the urban readership- ‘Lossit and last black house on island with hipped roof covered in thatch. Note roof of byre next door is upturned boat’. This croft house also features in the islanders’ own photographic collections, in particular the Katie Maclean Collection, with family connections to the MacQuarries, which denotes ‘Donald MacQuarrie, wife Mary, children and Ishbel MacQuarrie lived here’. Ishbel MacQuarrie is photographed here as she is a relative who is part of a family. Therefore, the photograph was taken with different reasons- to record the actual person and her significance to the related photographer. The Eigg History Society photographic archive provides a significant collection for study of local history and how islanders documented themselves and their surroundings.

MEM Donaldson’s photograph of Ishbel MacQuarrie features on the cover of Camille Dressler’s book ‘Eigg, The Story of an Island’

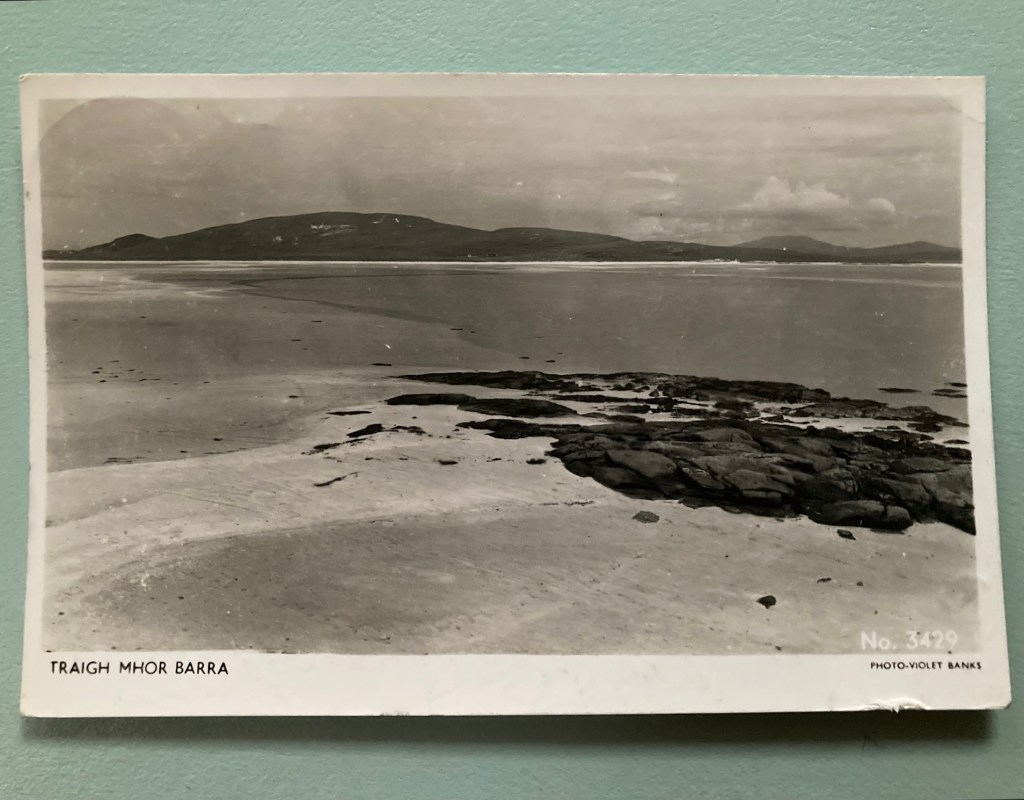

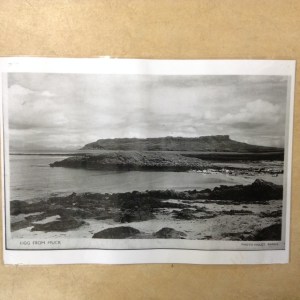

In 1935, Violet Banks established her own commercial photography studio in Edinburgh. Lucy Conway organized for me to speak about Donaldson and Banks with the Eigg History Society. At the event Camille Dressler identified that three of Banks’ photographs of Eigg, that appear in her photograph albums held by RCAHMS, are also held as facsimiles of postcards in the archive. The copies show images of Laig Bay, the Sgurr and a view of Eigg from the Isle of Muck, all bearing the credit ‘Photo: Violet Banks‘. This provides another use of Banks’ images, for commercial purposes, and another line of enquiry to follow up, in looking for the original postcards.

‘View of Eigg from Muck, Photo: Violet Banks’, photocopy of postcard, Eigg History Society

Footnotes

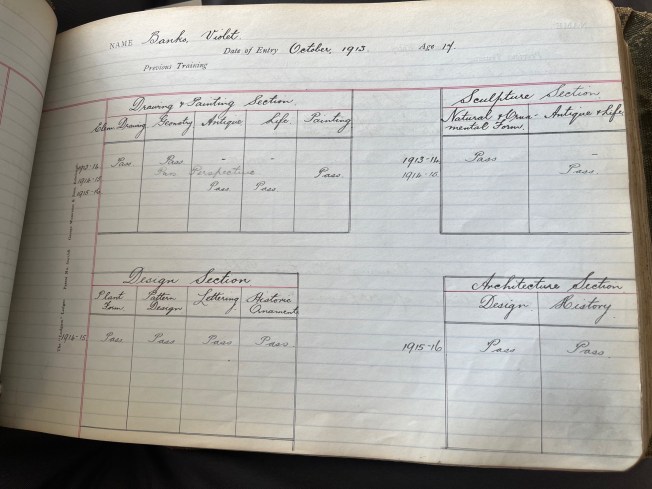

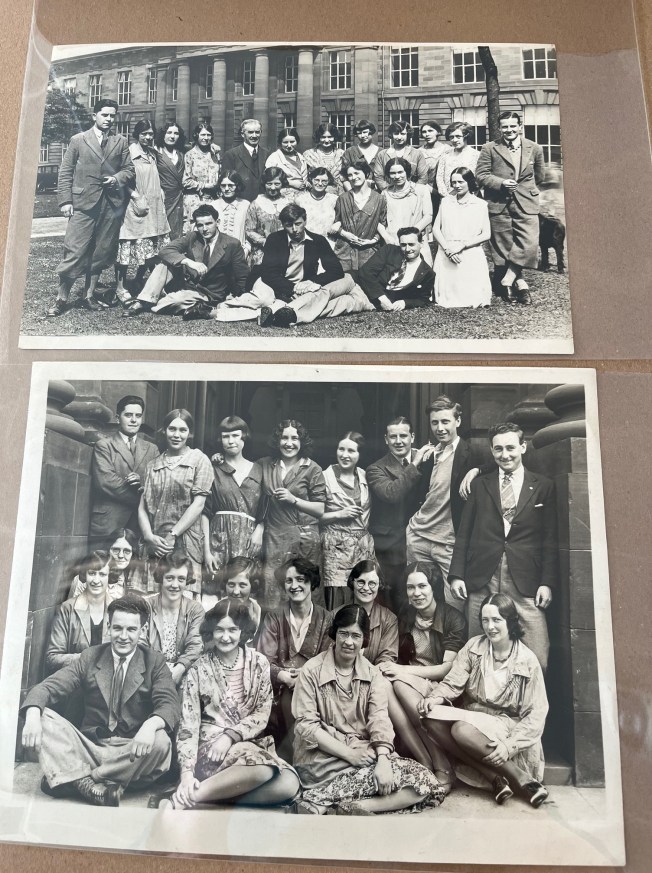

[1] Veronica Fraser, an archivist at Royal Commission on the Ancient & Historical Monuments of Scotland writes about Banks’ life in ‘Vernacular Buildings‘:

‘Violet Banks (1986-1985) was born near Kinghorn, Fife and educated at Craigmont, Edinburgh, and at ECA (Edinburgh College of Art). In 1927 she was senior arts mistress at St. Oran’s, a private school at Drummond Place, Edinburgh‘.Banks’ photographs of the Hebrides, Fraser recounts, were discovered by John Dixon of Georgian Antiques, in a drawer in a sideboard that had been part of a furniture purchase and then gifted to RCAHMS to become The Violet Banks Collection. P67-78, ‘Vernacular Building 32′, Scottish Vernacular Buildings Working Group 2008-2009) ISSN:0267-3088.

[2] ‘Eigg The Story of an Island‘, Camille Dressler (Birlinn Ltd 2007, 3rd edition)

[3] ‘The Walking Library’ for Bothan Shuibhne, Isle of Eigg, is a project by Dee Heddon and Misha Myers, with this particular iteration in 2013. The ‘Walking Library’s‘ aim is to bring together books on walking and its contemplation, and is a collective gathering of book recommendations from those that accompany Heddon and Myers on a walk, in this instance from Carbeth Community Huts to the Walled Garden, with Sweeney’s Bothy in mind.

[4] P.104, ‘Eigg, The Story of an Island’, Dressler, C.

[5]’The Geology of Eigg‘, John D Hudson, Angus D Miller and Ann Allwright, Isle of Eigg Heritage Trust, (2014, Second Edition) is part of the ‘Waking Library’ at Sweeney’s Bothy and accounts for the rock formations of Eigg.

[6] P.45, ‘Herself and Green Maria: the photography of M.E.M. Donaldson’, Cheape, H, ‘Studies in Photography’ (2006)

[7] P.50, ‘Eigg, The Story of an Island‘, Dressler, C, (2007, Birlinn Ltd, 3rd Edition)

[8] P.7, ‘Eigg, The Story of an Island’, Dressler, C, (2007, Birlinn Ltd, 3rd Edition)

[9] P.45, ‘Herself and Green Maria: the photography of M.E.M. Donaldson’, Cheape, H, ‘Studies in Photography’ (2006)

[10] P.4, ‘Eigg, The Story of an Island’, Dressler, C, (2007, Birlinn Ltd, 3rd Edition)

[11] P.98, ‘The Small Isles, Canna, Rum, Eigg & Muck’, Rixson, D, (2011, Birlinn Ltd, 2nd edition). Copy in Sweeney’s Bothy’s Walking Library.

[12] Donaldson’s photograph of Ishbel MacQuarrie ‘gathering the peats’ is also the cover image of Dressler’s ‘Eigg, The Story of an Island’.

With thanks to: The Bothy Project, Lucy Conway & Eddie Scott, Eigg Historic Society, Camille Dressler.

Sweeney’s Bothy, Isle of Eigg, The Bothy Project Photo: Jenny Brownrigg (2016)