Into the landscape, M.E.M. Donaldson

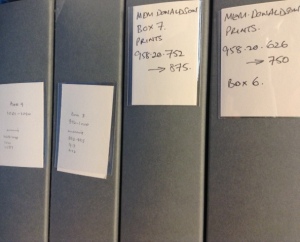

Over one thousand photographs by author and photographer Mary Ethel Muir Donaldson [1876-1958] are held by Inverness Museum and Art Gallery as part of the Highland Photographic Archive . The collection was gifted by the widow of Donaldson’s biographer and custodian John Telfer Dunbar. Inverness Museum and Art Gallery holds Donaldson’s landscape photography, whilst National Museums Scotland has the original negatives and prints of the portraits she took of the people she encountered over the Scottish Highlands and islands.[2]

For the purposes of this post, I would like to concentrate on the Inverness part of the collection. Out of the three women I am researching- M.E.M. Donaldson, Margaret Fay Shaw and Jenny Gilbertson – Donaldson covered the widest range of Scottish landscapes and locations. Donaldson wrote guides, for which her photographs often illustrated, including ‘Wandering in the Western Highlands and Islands‘ (1921) and ‘Further Wanderings-Mainly in Argyll’ (1926). In the Inverness collection, island locations include Eigg, Skye, Oransay, Colonsay, Islay, Jura and Iona. From the Highlands there are photographs of Kintyre, Kintail, Wester Ross, Appin, Arisaig, Glen Affric, Lochaline, Loch Linnhe, Ballachuilish, Kingussie, Glen Affric, Roy Bridge, Knapdale, Morvern, down into the Trossachs. The collection also has a focus on Ardnamurchan, in particular at Sanna, where Donaldson built her house in 1927, complete with photography studio, and lived there until 1947. [3]

Whilst looking through the Inverness Collection, at landscape after landscape, I began to think of Nan Shepherd [1893-1981] who wrote about the experience of the landscape being a physical and psychological journey ‘into’ (in Shepherd’s case, the Cairngorms) rather than merely a simple passage over on the way to an endpoint. Using this reading, Donaldson’s landscapes are not composed as passive views to be looked at; they are to be journeyed into. The photographs circle lochans, dip into glens and cross plateaus. In particular ‘In Glen Carrich’ has a sequence of photographs that show the terrain unfolding. The eye traces the route in front of the camera, spotting the gap in the stones in the foreground, cutting round the corner of a rocky mound, tracking left around the hill with the three trees to the hidden landscape beyond. In others, a device such as a meandering burn, an intermittent path or rough track takes you further into the photograph. Donaldson wrote:

‘Certainly to a lover of the wild, the monotony a level stretch of high road, with its dull, even surface, doubles the distance, while the interest of a constantly varied and often ill-defined track, full of surprises and with a marked individuality, seems actually to halve the distance.’[P.142]

The sharpness of Donaldson’s photographs also encourages this level of active looking. From her photographs in the Cuillins, the lines of the ravines on the flanks of the mountains in the background are as precise as the sheen of the wet stones of the plateau that gently coruscate in the foreground. Shepherd describes a changing the focus of the eye, and the ego, to see the landscape anew: ‘As I watch, it arches its back and each layer of landscape bristles… Details are no longer part of a grouping of a picture around which I am the focal point, the focal point is everywhere… This is how the earth must see itself.’[5]

Shepherd talks in ‘The Living Mountain’ [6] of the mountains having an ‘inside’. Throughout the Inverness collection of Donaldson’s photographs there is a series of studies of cave mouths including Cathedral Cave and St Francis’ Cave on Eigg, Fingal’s Cave in Staffa and Prince Charlie’s Cave , at Ceannacroc, Glenmoriston. Whilst Donaldson undoubtedly visited the caves for their history and associated stories for her books, the photographs themselves, freed of titles and any references again suggest the desire to go ‘into’ the landscape. Indeed, one portrait of MEM Donaldson, shows her with just head and shoulders remaining above ground. The other people who are in these photographs really inhabit the landscape too. Caught in the middle distance or far distance, any figure that appears in the Inverness collection is part of the landscape that surrounds them. A tall, thin man stands in the empty ‘o’ created by a rock formation. Two people are mysteriously held in the deep channel created by two massive boulders.

How does Donaldson’s photographic treatment of the highlander or islander differ in the Inverness part of the collection from the portraits in Edinburgh? In one Edinburgh example, there is a close up in profile view of a seaweed gatherer, bent with the weight of the load he carries in a basket on his back. In another photograph from the Inverness collection, Donaldson has zoomed out, placing this figure in the landscape. His figure can been made out on the beach, framed by rocks in the foreground, and showing the contours of the island of Rum beyond. By reducing the scale of the figure and placing him within the landscape, as the viewer we see how far he must walk, and therefore the physicality and difficulty of his labour.

Shepherd writes of an embodied knowledge, where touch, taste and experience are the agents of her understanding the environment. Donaldson also placed an emphasis on a physical sense of her body, and often mind, in the landscape. Her books ‘Wanderings of the Western Isles’ and ‘‘Further Wanderings-Mainly in Argyll’ are full of descriptions of how she traverses different terrain. In her fictional book ‘Islesmen of Bride’ (1922, Alexander Gardner, Paisley), the unnamed narrator who is the main protagonist could be read as intriguingly genderless, with other characters never refer to the narrator as a man or woman. The narrator takes on the rowing of the boat to the island ferry for a summer, is involved in heavy labour and crosses great stretches of the islands on foot. Donaldson’s own desire to walk and be active can be directly aligned with her own sense of freedom, which was thwarted in her childhood as she was a female. In 1929, she wrote to Marion Lochhead:

‘I have always had a hard life, for I never was one who could fall into any sort of conventional moulds… My fervent desire in those days was to be a boy who could run away and be a gypsy always living in the open.‘ [7]

Her landscape photography therefore takes on poignancy, as a place where Donaldson felt closest to her ‘founding spirits’. [8] Again in ‘Wanderings of the Western Isles’ Donaldson writes:

‘The mountain lover finds solely amongst the mountains what the sailor finds alone upon the sea – that sense of limitless freedom so essential to the well-being of the free spirit – life in its purest, simplest, physical sense.’ [9]

It should be noted that whereas Shepherd referred to a more ambiguous presence in the landscape, Donaldson attributed all to ‘the Creator’ [10]. A deeply religious person, the landscape was, for her, the place she could experience and be closer to God.

Donaldson corrects Marion Lochhead at the conclusion of a follow-up letter, dated 18 June 1929, having read a draft of an article for ‘Bulletin’ that Lochhead had wrote on her:

“I who have never left these shores, have never thought of myself as a ‘traveler’, but having looked it up in the dictionary and see one definition to be ‘a wayfarer’, in that sense the description is correct“.

Shepherd’s journeying was to return to the mountain’s foot hills time and time again, rather than to aim only for the summit, in order to continue her deep reading and connection with her surroundings. Through Donaldson’s wayfaring, her landscape photography communicates the physicality of the walk, of carrying her camera out and above all, her sense of freedom.

Footnotes

[1] ‘Herself’, DUNBAR, J.T. (1980) 2nd Ed, Ticknor & Fields, New Haven and New York.

[2] National Library of Scotland also holds copies of the portraits as part of the John Telfer Dunbar Collection.

[3] Donaldson lived at Sanna Bheag until 1947, when a fire destroyed her home.

[4] P. 142, ‘Wanderings of the Western Isles’, DONALDSON, M.E.M. (1921), Alexander Gardner, Paisley.

[5] P.10-11, ‘The Living Mountain’, SHEPHERD, N. (2011) 3rd Edition Canongate Books

[6] Ibid. Shepherd wrote ‘The Living Mountain’ in 1945, but it was not published until 1977 by Aberdeen University Press.

[7] Letter from M.E.M. Donaldson, to Marion Lochhead, dated ‘St Columba’s Day, 1929’. Letter held by National Library of Scotland.

[8] Ibid.

[9] P. 141, ‘Wanderings of the Western Isles’, DONALDSON, M.E.M. (1921), Alexander Gardner, Paisley.

[10] P.141, Ibid.