“The one thing I am afraid of is moths.”

The moths are in the tall turret, wrapped up in the green leafy carpet that climbs up the stairs. By torch light, we see them flit, contained in their own vertical cosmos, well beyond the stately rooms. We climb up to the highest point, gingerly stepping up and out onto the flat, flexing zinc, to look over the balustrade, past the concertina of tiled roofs to the horizon line beyond. A ship tanker lined in white fairy lights, glides from left to right, as the more adventurous of us rattle doors, on our quest to learn the layout of the house’s many passageways or to scare the ghosts. In one of the books lifted from the Library shelf, the writing on the page is so tiny, that the black ink coalesces to nearly cover the white.

The common clothes moth tineola bisselliella when caught between fingers turns to a gold dust, causing the sheerest cast of light over the ridges of fingerprints. The chine-collé printmaking technique sees an image transferred to a thin surface which has been bonded to a heavier support. The lighter paper pulls the finer detail from the metal plate. A print, now unwrapped and placed carefully on the studio table, has travelled from Dundee to Brazil and back. A subtle golden sheen embedded within the weight of the pressed black panes, causes a shimmering light to dance through the scratched inky darkness. The print now travels to Glasgow as a gift.

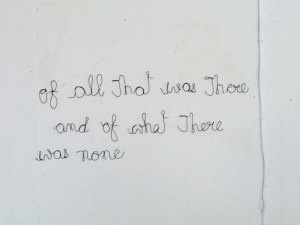

‘Of all that was there/ and of what there was none’. This house is a strange compression in time. In the Cedar Room, a man from another period holds a clay bowl, which has been simply made from coils and decorated with circles. On a shelf next to this portrait, this exact clay bowl sits in amongst the detail of the room. The bowl exists as both a painted artefact and a real object. Over in the artists’ studio, another bowl sits, perched on the head of a hovering blue body. What kind of spell is this?

A bump, the bus lurches and stops, reminding two of us of their journeys through India. A body moves involuntarily from back to front seat. Bang! A goat is held. Wheels dangle over the cliff edge. A man is hit. Don’t worry, we are the mountaineers! Now see this yellow transparent cloth suspended from the ceiling, in the studio. It is the cloth she picked up in India. The recent shared stories have served as a marker for her to return to this once visited place, through her work. Look through the material’s lined pattern and see the happy detritus of this space of making, from the man with his love of art who began it, to the present occupant. His plaster busts line the mantle. She makes her own discreet whittled objects as an everyday exercise. Half torsos here, a sewing needle there. All are in constant motion and rearranged, until they too come to a pause, resting on the curve of a pregnant belly, hidden in a unisex white office shirt.

A conversation begins on cadavers. A pencil presses too hard, then too light on the paper. It is hard to commit to the tracing of death. Another of us conducts a digital examination of Deleuze’s corpus. It is not about ‘being’ but ‘becoming’ (devenir). The action lies in the flow and the space in between, until it stops.

A row of static caravans, so neat and so ordered. Surely these oblongs are shaped to hug the landscape and horizon. A different kind of static, to the ones she has known, so it must be recorded onto reed paper. This image awaits its turn with others, ready to be suspended in the white curved track, to become a painted length of film.

Look up and see the golden light and the turned soil of the field through the window. Flatness becomes animated. Hands are helped in order to gesture silent words. They make for a strange yet moving couple, the child-like puppet who sits in the woman’s lap, out in the field. Indoors, the watercolours of their words and actions lie under the studio table. Again, a further step back in time into the bedrooms of young German Princes. The portrait of another couple, divided by age, hangs on the wall, warning youth of the outcome of hurried choices. Another of us dreams about this ill-matched couple.

Now in the courtyard, a small wire-haired dog dances in the concrete trough, his movements as exact as a puppet, disturbing the black water and green weeds through the regular rhythm of its paws. One door swings shut, locking out the dweller. A man climbs a ladder and moves through the window gap. His legs can be seen by the audience below, with toes slowly pointing, as they slide gracefully from view. Meanwhile a whippet opens other doors, without a care, nor good reason, but to dance on steel surfaces. A woman, with great care, places fresh flowers from the garden, onto tables throughout the house and forgets a pile of runner beans.

The Latin beat of Nosce te Ipsum is carved into the fireplace of the Picture Gallery, originally Plato’s maxim inscribed on the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. There are many translations here in our house, from Norwegian into Croatian, whispered through the grand halls. The translator follows the paths by day that her words take at night. She stops to admire blue wallpaper as seen in mirrors, or meet the outstretched hands of the figures in the tapestries. Another figure, another night, this time in white silk, moves through the house and up the stairs. An out of tune pianola plays.The leaves wind around the house’s ornate stone pillars. A stone tortoise takes refuge in the column’s base.

Another, whose name means Flax in Sanskrit or Bright in Hindi, methodically turns garden wire, then lengths of white paper, in her hands, and the gentle shapes of leaves begin to cascade. Raw material falls into the shapes they cannot refuse.

The house’s dwellers and visitors act as an encyclopaedia for each other as connections and new views are cultivated in a spirit of generosity. A film, ‘Solar Breath’ (2002) by Michael Snow, is recommended. For the film’s duration, as the cabin inhales and exhales, the curtains at the window rise and fall, to reveal the solar panel outside that fuels the camera and the enterprise. A continuing circulation of ideas, conversation and actions fuels this particular house. The people within make an almighty collaborative generator which continually transfers energy from the original owners to the those who care for and guide this place and its inhabitants; to those that are invited to share a fragment of time within its walls. Several rivers flow through. One leads to Venice; another winds from India to Scotland and back. A smaller, regular tributary carries the willing recipients’ stomachs and mouths from work to dining table and back.

The last mystery: “Do all Canadians know each other?”

‘A Story to be Read in a Tower’ was written following a week spent with Hospitalfield Arts Interdisciplinary Residency practitioners in Arbroath, Scotland (Aug 2014): Mireille Bourgeois (CA), Yael Brotman (CA), Christine Goodman (UK), Libby Hague (CA), Birthe Jorgensen (UK), Anja Majnaric (HR) and Uma Ray (IN). The story picks up on what each person was working on at Hospitalfield Arts, along with fragments of conversations and experiences of the week spent together.

Jenny Brownrigg, August 2014