Salutations, Margaret Fay Shaw

Front door, Canna House Photo: Jenny Brownrigg

Mrs Shaw Campbell, Mrs John Campbell, Dear Mrs Campbell, Dear Mrs Lorne, Dear Margaret, Dear Margarita, Dearest Maggie, Maggie love, Dear Meg, My dear Meg, My dear dear Meg, Dearly beloved Meg, Dearest Marge, Dearest Marcat.

These salutations are on letters addressed to Margaret Fay Shaw (1903-2004) ranging from the formal to the diminutive. These letters, both business and personal, were sent from all over the world and are part of a significant archive at Canna House, on the Isle of Canna, where Margaret Fay Shaw lived with her husband John Lorne Campbell. Both sought to record the everyday life of people living in the Hebrides. Whilst John Lorne Campbell specialised in capturing the spoken word, in order to understand everyday Gaelic and its dialects, Margaret Fay Shaw focused on transcribing Gaelic songs and recording Hebridean island life predominantly through her photography.

Shaw, as a single woman, spent six years from 1929-35 living with the sisters Peigi [1874 -1969] and Màiri MacRae [1883 -1972] at their croft at North Glendale, South Uist. Màiri MacRae was forty-six and Peigi, fifty-five, when a twenty-six year old Margaret Fay Shaw arrived. Indeed, as Shaw’s own ‘amanvensis’ Magdalena Sagarzazu [1] narrates in her introduction to the book ‘The Voices’ by Alex MacRae [2], this time was so significant for Shaw, (leading to a continued friendship with the sisters), that she chose to be buried next to them: ‘Margaret Fay Shaw was buried beside her two friends and among the people of South Uist she loved so well at Cladh Halainn cemetry’. [3] Shaw recounted during the programme ‘Tir A’ Mhurain’ that Peigi and Màiri MacRae, ‘… taught me more than university, they were the most interesting and knowledgeable women’. [4]

A trained musician, Shaw’s primary motivation to move from New York to South Uist was to transcribe Gaelic songs at their source. In her own words, she ‘… chose South Uist, as the island least visited by strangers and where there would be an opportunity to live amongst a friendly and unprejudiced people not self conscious of their unique heritage.’ [5]

After hearing Màiri MacRae sing at Boisdale House on her arrival in 1929, she was invited by Màiri to learn the song by visiting her at home in Glendale. On making the journey to their croft, which was two miles from any road and easier accessed by boat, Shaw asked if she could lodge there. Over the next six years Shaw transcribed the MacRae’s songs and those of their neighbours, further learning Gaelic over this period too. Michael Russell in his book ‘A Different Country: The Photographs of Werner Kissling’ attributes Shaw’s knowledge of Gaelic- ‘almost unique[ly] amongst photographers who worked in the Hebrides’ – as a way ‘to penetrate Hebridean culture more thoroughly and to get closer to the rhythms of place’. [6]

With her Graflex camera (the first on loan for two years from her brother-in-law Boone Groves until she was able to buy her own) and 16mm Kodak movie camera, Shaw photographed and filmed the Glendale community at work and at leisure. She did not own a light meter or tripod at that point: ‘I used piled up rocks for support or got someone to crouch on all fours while I balanced the camera on their back’. [7] Whilst a photographer such as Paul Strand, who over three months of the summer of 1954, made single monumental portraits of South Uist islanders, [8] Shaw focussed on a single community and recorded it in its detail. The time shared with the MacRae’s and their neighbours allowed Shaw to take numerous photographs, in particular of Màiri MacRae. Shaw records her digging the field with her son Donald; sything the oats with her sister Peigi; and shearing the sheep.

Like Shetland film maker Jenny Gilbertson [8], through the prolonged period of time spent living on a croft, Shaw was highly aware of its seasons and cycle. She records both in her diary, her transcript ‘The Outer Hebrides’ and subsequently in her life work ‘Folksongs and Folklore of South Uist’(1977):

The spring work of the croft began in February, when seaweed, used as fertilizer, was cut with a saw-toothed sickle called a corran on the tidal islands of the loch at low water of a spring tide’. [9]

The year closes with: ‘All the harvest work done, the women wash and card the wool and start the spinning wheels. It is the season for the fireside and the ceilidh, the rough weather and the short days.’ [10]

Beyond the archetypal image of crofters at labour, also denoted by other photographers and film makers of the era such as Werner Kissling (1895-1988) or Alasdair Alpin MacGregor (1899-1970) [11], Shaw’s photography goes further, recording everyday domesticity as well as the special occasion on the croft. In one photograph, Màiri MacRae stands in her doorway and holds a gifted salt cod up by its gills. The fish is viewed avariciously by the cats at her feet, with one reaching up to snatch at the fish’s tail. In another, Angus John Campbell sits with Màiri MacRae by the fireplace in an interior shot. The second of this short sequence shows him still seated next to MacRae and playing an accordion.

The sisters and their neighbours are often photographed in social situations and gatherings outdoors, one of these scenes being a tea party with Màiri MacRae, her son Donald and Peigi MacRae who all kneel on a white sheet that has been laid out on the grass. This gathering looks ceremonial; Màiri MacRae holds a china teacup with her left hand, raising it to camera, whilst her right hand keeps a hold of a sleeping cat who looks in danger of slipping off her knee. Peigi MacRae holds the teapot in her right hand and bannock in her left. Donald, the most surprising of the trio to contemporary eyes, sits in the middle with their dog Queenie. Whilst the man of the house, he looks barely in his teens in this photograph, but has a pipe in his mouth. A white piece of laundry can be discerned in the background. Like the snowcap of a mountain, it is laid out on the stone wall to dry in the sun.

The sound of the everyday is also wonderfully evoked by a typed document from Canna House Archives entitled ‘South Uist in Sound’ [12] where Shaw lists ‘characteristic sounds’ under headings including ‘Birds on the shore’, ‘The beasts of the croft’, ‘Conversations’ ‘Transport’, ‘The shop’, ‘Dancing’, ‘Songs and stories’ and ‘Agriculture’:

‘Inside the cottage.

Milking, churning, mending shoes, noises above the stoves, lids rattling, kettles boiling, setting dishes, spinning heel, carding (with appropriate songs), the loom and wool winders, the bucket to the well and back, washing clothes and ironing, noise of children, primus stoves and tilly lamps; clocks ticking, rats scuffling in the walls, cats growling under the dresser, dogs being cursed and told to lie down (in Gaelic), scratching fleas.

Magdalena Sagarzazu believes that the photographs cannot be viewed alone without relating them to music and culture; they sit holistically within a wider context. This is borne out through Shaw’s pencil notations on the songs’ original music sheets, held as part of the Canna House archive, as well as the printed transcriptions in Shaw’s ‘Folksongs and Folklore of South Uist’ where tune, words and sometimes composition are attributed to those who appear in her photographs from the Glendale community. For example, ‘Óran Fogarraich – An Exile’s Song’: ‘The tune, chorus and first verse from Miss Peigi MacRae, the second and third verses from Angus John Campbell.’ [13] Shaw records for most songs how the singer learnt the song: ‘Miss Macrae learnt the song from Miss Catriona MacIntosh while employed at Boisdale House when a young girl’. [14] The excellent online resource ‘Tobar an Dualchais’ contains original recordings of songs sung by Màiri MacRae and Peigi MacRae, that were recorded at a later date by Campbell and Shaw when recording equipment was available. It also contains an extract of a song ‘Oran a’ Chutaidh’, sung by Donald MacRae, about a dog.

Canna House, The National Trust for Scotland Photo: Jenny Brownrigg

The word ‘source’ crops up often in researching and thinking about Margaret Fay Shaw and John Lorne Campbell’s collection and archive at Canna House. The ‘source’ is the singer, the landscape, language, stories and lives. Martin Padget in his book ‘Photographers of the Western Isles’ [15] notes Shaw’s quest for authenticity, referencing the first occasion Shaw heard a Gaelic song, sung by Marjory Kennedy-Fraser (1857-1930) [16] and wishing that she could hear the song in its raw state sung by the original island singers. The idea of authenticity and source also follows through to Shaw’s photography and her films, the latter which remained as unedited film rushes, purely made for her and the community’s enjoyment, until later television programmes on Margaret Fay Shaw used this footage. [17]

Furthermore, the very fact the archive is held at Shaw and Campbell’s home at Canna House means it is also kept at ‘source’, rather than in another repository on the mainland. This was not the Campbell’s holiday home but their only home, each room a collection in itself. All has been left as if the couple have just stepped out for a few moments. This condition, gives the opportunity when researching the archives at Canna House to feel closer to the life’s work of Margaret Fay Shaw, John Lorne Campbell and the lives of those that they recorded.

With thanks to Fiona Mackenzie, archivist at Canna House and Magda Sagarzazu, retired archivist, Canna House.

Footnotes

[1] Magdalena Sagarzazu, retired archivist, Canna House, The National Trust for Scotland. Margaret Fay Shaw called Sagarzazu her ‘amanvensis’: a person employed to write or type what another dictates, or to copy. From an interview with Sagarzazu, 2014.

[2] ‘The Voices’, MAC RAE, A. (2010) Elk Classic Publishing. Alex Mac Rae is the son of Andrew Mac Rae and compiled the book ‘The Voices’: ‘Through a chance meeting with Margaret [Shaw], Peigi and Mairi’s nephew Andrew Bei Mac Rae was encouraged to record the ways of life of his family through images and sound. So he did and captured life in the 60s and 70s.’

[3] Ibid, P3.

[4] ‘Tir A’ Mhurain: Margaret Fay Shaw’, (9.3.89), TV programme.

[5] P10, ‘The Outer Hebrides: Margaret Fay Shaw’, SHAW, M.F. Undated. Typescript held at The National Trust for Scotland, Canna House.

[6] P32, ‘A Different Country: The Photographs of Werner Kissling’, RUSSELL, M. (2002), Berlinn Ltd.

[7] P4, Typescript of the Aran Islands, SHAW, M.F. 12 July 2002. Typescript held at The National Trust for Scotland, Canna House.

[8] ‘Tir A’ Mhurain: The Outer Hebrides of Scotland’, STRAND, P. (2002) 2nd Ed. Aperture Foundation.

[9] Jenny Gilbertson (1902-1990) was a filmmaker who in the 1930s’ began living on a Shetland croft, making documentary films about life in Shetland. She took up her film-making again in the 1970s’, where she went to live in the Canadian Arctic.

[10] P 96, ‘Folksongs and Folklore of South Uist’, SHAW, M.F. (2005) 2nd Ed. Birlinn Ltd.

[11] P21, ‘The Outer Hebrides: Margaret Fay Shaw’, SHAW, M.F. Undated. Typescript by Margaret Fay Shaw, held at The National Trust for Scotland, Canna House

[12] Alasdair Alpin MacGregor had an ongoing spat with Shaw, her husband John Lorne Campbell and Compton MacKenzie over their differing perspectives on how Hebridean islanders were depicted. This came to a head following the publishing of MacGregor’s book ‘The Western Isles’ (1949, Robert Hale Publishers) where MacGregor ‘endeavoured to give a contemporary account of the Islanders and their ways, free from any “nebulous twentieth-century impressionism”’ (preface, ‘The Western Isles’). MacGregor called the islanders lazy: ‘The characteristics of the people which the stranger to the Western Isles is swift to observe, certainly so far as the male population is concerned, are laziness and drunkeness. Many of the islanders are now so indolent and so spoilt by easy money that they no longer deign to cut peat, even though it is to be had on their own crofts.’ P234, ‘The Western Isles’. A letter from Shaw to MacGregor, held at Canna House, reads: ‘You ask me for an assurance not to express my opinion either by word of mouth or by writing. My letter to your publisher will be my writing. Of my speech I will condemn your book and your action in writing as long as I live’. (Jan 1950).

[13] P5, ‘South Uist in Sound’, SHAW, M.F. Undated. Typescript held at The National Trust for Scotland, Canna House.

[14] P96, ‘Folksongs and Folklore of South Uist’, SHAW, M.F. (2005) 2nd Ed. Birlinn Ltd.

[15] Ibid.

[16] P126, ‘Photographers of the Western Isles’, PADGET, M. (2010) John Donald, an imprint of Birlinn Ltd.

[17] Marjorie Kennedy-Fraser was a professional Scottish singer, composer and arranger. Including songs she transcribed from Eriskay, Kennedy-Fraser made three volumes of ‘Songs from the Hebrides’ published between 1909-1921.

[18] ‘Among Friends: Margaret Fay Shaw’, (2003) made by Mòr Media for BBC Scotland, and directed by Les Wilson. This programme was made to celebrate Shaw’s centenary.

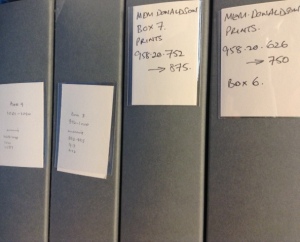

This Research Note is part of my Glasgow School of Art Research Leave project ‘Documenting 1930s’ Scottish Highland and Islands Life: M.E.M. Donaldson, Jenny Gilbertson and Margaret Fay Shaw’.

Looking out to the bay from Canna House garden Photo: Jenny Brownrigg